(翻譯內容以英文版本為準)

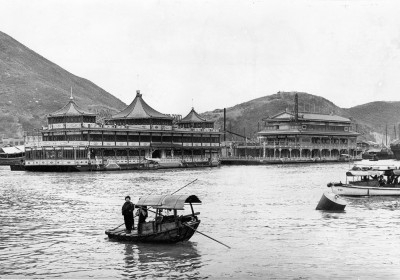

上週蘇格蘭的聖安德魯斯大學舉辦了一場進階指揮研習課。課程安排了來自世界各地的 8 位新晉指揮家前來學習,並安排了學校的榮譽教授 Sian Edwards 任教。我幸獲挑選為其中一位參與課程的指揮,成為我所屬大學首名獲邀參與該課程的學生。其餘 7 位指揮家則來自世界各地,近至德國、意大利和奧地利,遠至日本及哥倫比亞。

研習課開始前,我做了一些關於其他 7 位指揮家的資料搜集,他們的履歷令我大為驚豔。他們不止擁有自己的網站,更曾經參與無數指揮比賽及研習課,更有與專業管弦樂團、歌劇團合作的機會。作為 8 人之中經驗最淺的指揮,很希望這次難能可貴的學習經歷,能鞏固並拓闊我的指揮技巧,並藉著這次機會,作為我來年繼續深造的跳板。

負責任教研習課的專業指揮 Sian Edwards 是一位受國際稱譽的指揮家。她於 1984 年於著名的列斯國際指揮比賽中首次獲獎,是國際間少數能在古典音樂界站穏陣腳的女指揮家。Edwards 曾任英國國家歌劇院的音樂總監,並與無數領先的管弦樂團合作,如倫敦愛樂樂團、洛杉磯愛樂樂團、法蘭克福廣播交響樂團、維也納交響樂團以及克利夫蘭管弦樂團。

經過 3 天研習課,Edwards為我帶來無數、無價的寶貴意見,以指導和改善我的指揮技巧,身體語言以及與管弦樂手的溝通。她的智慧與經驗成為我重大的啟發。Edwards 充滿智慧的言辭深深啟發了我,令我學會如何演繹、明白及欣賞樂譜。

另外,指定研習劇目風格廣泛,能鼓勵 8 位指揮家在更多類型音樂中摸索,例如管弦樂有貝多芬的「第 8 交響曲」;弦樂有阿倫斯基版本的「柴可夫斯基主題變奏曲」;歌劇有莫札特的「費加洛的婚禮」;以及令人振奮的當代作品,英國作曲家 Errollyn Wallen 的「攝影(Photography)」。

新晉指揮家趨向模仿大師的行為及動作乃常見之事,例如過度移動身體,或以過於戲劇性的姿態來指揮。Edwards 提醒我們「做回自己」的重要性,在早期的指揮事業,應該保持謙虛。無容置疑,那些傑出的指揮家,他們華麗的行為往住能讓觀眾神往,更能成為觀眾追隨他們的誘因。然而,作為新晉指揮家,我還沒取得重大成就,未在古典音樂世界中站穩陣腳。我應該要保持謙虛有禮,亦要不斷提醒自己:指揮家的職責是為音樂服務,而不是在舞台上表演得誇張、狂妄自大。畢竟,要判斷一位指揮家的優劣是從他/她對音樂的解讀與表現,而不是透過其動作或外表來判斷。

指揮研習課在 Edwards 指導下,進行了三天密集式培訓。在首兩天,8 位指揮家只有機會在大家面前指揮一名鋼琴家,直至第三天,研習課集合了一支小型管弦樂團,需要幾位指揮家共同合作。當初承諾至少會有 10 位專業音樂家與當地樂手一起合奏,但現實教人大失所望:在舞台上的 22 位音樂家中,幾乎沒有一位能稱得上是專業樂手。他們當中大多數是半職業樂手,更有不少是已退休的老年樂手。另外,一些大學生被選入樂團,就連 3 位與參與課程的指揮也被要求在樂團中演奏 —— 我就是其中之一,在不需要指揮時負責敲擊定音鼓。

在場的大部分樂手都沒有為演奏做好準備,也沒有在事前好好練習,儘管他們有收取酬勞。他們的演奏生疏而粗糙,有時甚至會走音。事實上,他們犯的錯誤令人感到非常尷尬,導致指揮們蹙起眉毛,彼此交換了一個警惕的眼神。要在如斯情況下,一邊應用 Edwards 所教授的技巧,同時指導業餘樂手,無疑是一項艱鉅的挑戰。事後看來,我懷疑這是學院故意安排。畢竟,指揮這一群樂手能訓練我們的耐性和脾氣,提升我們與不同程度樂手合作的能力,亦讓我們學懂欣賞作為一個專業指揮家必須面對的挑戰,為將來做好準備。

The (Un)Professional Conducting Masterclass

Just a week ago, the University of St. Andrews in Scotland held an advanced conducting masterclass, which accepted eight emerging conductors from all around the world to study with Sian Edwards, the university’s Honorary Professor of Conducting. I was deeply honoured to be chosen as one of the participating conductors, becoming the first ever student from my own university to be invited to take part in this prestigious masterclass. The seven other conductors hailed from different parts of the world – from as far afield like Japan and Colombia and to closer countries like Germany, Italy and Austria.

Before the masterclass began, I did some research on the other seven conductors and was astounded by how experienced and accomplished they all were. Most of them not only have their own websites, but have also participated in numerous conducting masterclasses and competitions, and have been engaged by professional orchestras and opera companies. I was by far the least experienced conductor and hoped that this invaluable learning experience would consolidate and broaden my conducting skills as well as act as a springboard for more advanced learning in the coming years.

The professional conductor in charge of this masterclass, Sian Edwards, is an internationally acclaimed conductor. She is one of the very few female conductors in the world who is able to establish herself firmly in the classical music scene, ever since winning the first prize in the notable Leeds International Conducting Competition in 1984. She has held the music directorship of the English National Opera, and collaborated with numerous leading orchestras in the world, including the London Philharmonic, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Frankfurt Radio Symphony, Vienna Symphony and the Cleveland Orchestras.

Throughout the three days of the masterclass, Edwards provided me with numerous pieces of helpful and priceless advice on conducting that aimed to improve my techniques, accentuate the clarity of my body language and enhance my communication with orchestral musicians. Her confidence, aura and experience were a huge inspiration to me. Edwards’ words of wisdom were enlightening, which helped me to interpret, understand and appreciate the musical scores. Indeed, the assigned repertoire was wide-ranging and encouraged all eight conductors to explore and engage with a wide variety of music, from orchestral music like Beethoven’s Eighth Symphony, to string orchestra’s music like Arensky’s Variations on a Theme by Tchaikovsky, to operatic music from Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro and to Photography, an exhilarating contemporary piece by British composer Errollyn Wallen.

It is rather common for emerging conductors to emulate the actions and movements of the great maestros, such as moving our body excessively or conducting overly dramatically. Edwards reminded us the importance of being ourselves, of staying humble and of ‘keeping our feet on the ground’ in such early stages of our careers. Undoubtedly, the flamboyant actions of distinguished conductors often appealed to audiences and contributed to their cult following. However, as a burgeoning conductor, I have not yet attained great successes or established myself in the classical music world. I should remain humble and courteous, and need to continuously remind myself that the conductor’s main job is to serve the music, and not to look like an extravagant and theatrical egomaniac on stage. After all, a conductor is always judged by his/her interpretation and performance of the music, and not by his/her actions, movements and looks.

This conducting masterclass involved three days of intensive study with Edwards. For the first two days, all eight conductors only had the opportunity to conduct a pianist in front of them, and it was not until the third day that a small orchestra was assembled for the conductors to work with. While conductors were promised an instrumental ensemble with a minimum of ten professional musicians playing alongside local musicians, the reality was an utter disappointment. Out of the twenty-two musicians on stage, hardly anyone could be considered as a professional musician. The majority of them were semi-professional musicians, and quite a few were retired elderly musicians. In addition, some students from the university were drafted into the ensemble, and three of the conductors participating in the masterclass were also required to play in the ensemble – I was one of them and played the timpani throughout when I was not conducting.

Most of the musicians present were unprepared and did not practise the music beforehand, despite being paid for their services. Their playing was rusty, unsophisticated, rough, out-of-tune and unrefined. Indeed, some of their mistakes were embarrassing which led to the conductors raising their eyebrows and exchanging wary looks with each other. It was an enormous challenge to conduct an ensemble of this calibre, apply the techniques that Edwards taught us and help to coach the amateurish musicians, all at the same time. In hindsight, I wonder if this was intentional? After all, conducting this group of musicians trained our patience and temper, developed our ability to work with musicians of different standards and allowed us to appreciate the challenges we must face as professional conductors in the future.