The traditional dichotomy(註 1)is intuitive and simple: facts and logic to one side, feelings and superstitions to the other, both relevant in some area of human life, but ultimately often also in contradiction.

It might not, however, be as simple as it looks: because ‘facts and logic’, that seem to go together so nicely, might in fact be in even bigger contrast than they, together, are to feelings and superstitions.

The basic issue is that facts are facts, they are just the way it is, full stop. Our reason and logical mind is not quite happy with this. The basis of reasoning is that everything has to make sense.(註 2)

“Science” as the human activity could be simply described as: reason looking at the way things are to make sense of them.

However ultimately “science” as the result should only depend on the facts, not on what we make of it.

Yet as a reasoning being, the human cannot accept ‘brute facts’. In finding something that doesn’t make sense in nature, we always look for an explanation. When our observations of galaxy clusters don’t fit Einstein’s field equations, we don’t just accept it as a brute fact, we must make sense of it somehow — we ‘invent’ dark matter.

If we were so unlucky to live in a nature that just doesn’t make sense, we would never even know, and try to make sense of it forever anyway — getting the science always slightly wrong.

Our enthusiasm for sense-making is so strong that it does not always centre around science at all. Throughout the centuries we have taken reason far beyond where empirical and scientific evidence would warrant.

Mathematics itself is by far more developed than any science has applications for, and some such applications are already debatable.

The whole discipline of Philosophy is proof of this, treating facts and science as nothing but yet another thing to make sense of in metaphysics. And it pushes well beyond anything in the scientific domain when it discusses God, Free Will, and the ultimate essence of the World — precisely what may lie beyond the bounds of empirical facts.

To do science well, we must put our mania for sense-making aside and take a hard cold look at the data, all the facts and only the facts.

However, even this conclusion is dictated by our reason: no fact can lead us any which way unless we make sense of it.

So, despite being by their very nature in deep conflict, science and reason have always been forced into an uncomfortable alliance.

陶傑點評

作者是意大利人,英文並非他的母語,但他在英國倫敦大學用英文讀哲學,取得一級榮譽,並得到獎學金,在原校攻讀博士。

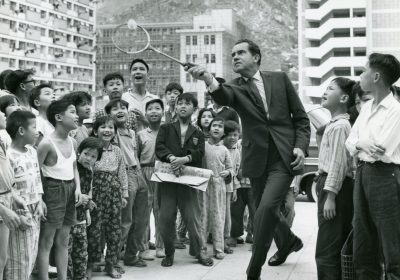

英語並非母語,能不能寫得好英文?俄裔演員烏斯蒂諾夫(Peter Ustinov)就可以。林語堂亦可。香港和台灣的年輕人,具備多少英文寫作能力?這是決定兩個地方的下一代能否融入國際的因素。

歐洲人用英文表達,優勢在於彼此文化根源相同:文藝復興、基督教、理性和科學的發展,令法國、德國、意大利等人進入英語世界思維,比亞洲人容易。譬如這一篇剖析「科學」和「理性」之間有何差異,一個 20 出頭的意大利大學畢業生,如何以英文表達,同齡的華人學生可以借鑒。

1.

- dichotomy:對立觀念 —— 黑白、陰陽、冷暖,還有理性與感性。作者指出:一方面為事實和邏輯,另一方面是感情與迷信,兩者往往互為對照。

- 但是作者認為,「事實」和「邏輯」之間的差異,往往大於「感情」和「迷信」的分別。因為:

2.

- 事實本身,有如一具屍體。屍體是一件物品,本身並不會說話,但是「邏輯」卻是對屍體的解釋,也就是尋找死因的演繹過程。因此,making sense,亦如「驗屍」,make sense,這兩個英文字,似乎很難有恰當的中譯,我認為就是中文裡的「格物」。

作者讀哲學,慣於抽象思維。我不讀哲學,我讀文學,文學講形象思維。因此我會將「屍體」喻為 fact,「屍檢」喻為 logic 。作者不會這樣講,因為他是一位學者。學者慣於寫論文,但專欄作者想到的,第一是如何與讀者溝通。因此,我認為作者以後的英文,如果面向大眾市場,不妨多用一點形象譬喻。

作者認為,「科學」(Science),就是對自然格物的一套綜合思考活動(reason looking at the way things are to make sense of them)。我認為,用形象譬喻說「科學是各學科格物的總匯」,也就是說:物理、化學、生物、地質學、航海,兄弟姊妹多人,都屬於「科學」這個大家庭;而哲學(philosophy)又在科學之上,是科學所需的純粹邏輯思考方法。科學有目的,就是研究世界;哲學好像有目的,就是思考物質世界以外的人生,但是沒有答案,也喪失了目的。

「科學」思考到「上帝」為邊界局限,哲學卻想超越此一邊界。科學如羅湖,哲學卻像大灣區和中國大陸。科學如地球,哲學卻像太陽系、銀河系、甚至宇宙。

「萬物」並無意義,能「格物」(make sense)才有意義。只有人才擁有格物的能力,然而人的大腦和智慧都有限,最多只能證明黑洞理論,但永遠無法探知生死的物理真相。這就是愛因斯坦會比叔本華更快樂的理由。

因此,如果你報考劍橋大學哲學系,可能遇到的面試題,就是:Einstein seemed to be a much happier man then Schopenhauer. Do you agree?

陶傑英文遊花園

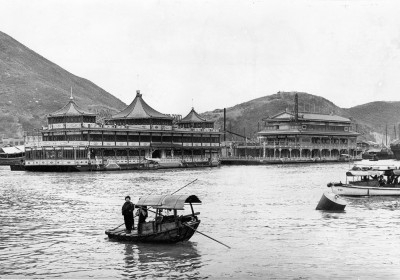

香港和台灣,面臨世紀的變局。海外華人居住西方國家,也數目龐大。如何提升英文程度,克服文化隔閡,加強英文能力,在亂世中至關重要。

許多華人都有合理的職業或專業的英文程度,但如何在原有的中學文法訓練基礎之上,探討高層次的英語文化和表達方式,以備融入英語世界主流社會?

本欄介紹評析欣賞英文的寫作細節,分享經驗,歡迎提出不同的評析角度和心得。