In the first three parts of my current series of articles on the musical qualities of the London Underground, I have examined eight of its eleven lines, including the likes of the vociferous Jubilee Line, the sluggish Circle Line and the ghostly Northern Line. This week, I will turn my attention to the remaining three tube lines on the network: Hammersmith & City, Metropolitan and Bakerloo.

Hammersmith & City Line

Printed in pink on the tube map, the Hammersmith & City Line connects Hammersmith in west London with Barking in the east of the capital. More than 99% of its tracks and each of its 29 stations are shared with three other tube lines, namely Circle, District and Metropolitan, all of which run much more regular services than the Hammersmith & City Line. As a result, the Hammersmith & City Line has often been overlooked and seen as the ‘little brother’ of the sub-surface tube network, and this is not helped by the fact that it also has the shortest length and fewest stations. I have heard a good number of times from fellow Londoners that they failed to see the purpose of the Hammersmith & City Line and called for it to be scrapped.

However, even though the Hammersmith & City Line might not be the most important and flamboyant of tube lines, it nevertheless has a fundamental function; that is, to connect Liverpool Street to Aldgate East, saving commuters the trouble from interchanging at Tower Hill and up to 20 minutes of journey time. This alone, for me at least, already makes its existence totally worthwhile.

The public’s frequent disregard of the Hammersmith & City line reminds me of the experience of Franz Schubert. Both his musical style and symphonic achievements are overshadowed by the other three members of the First Viennese School — Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. Although Schubert produced many phenomenal works, they have never been programmed as frequently as those by his three more distinguished colleagues, nor are they as revered by the general public. In particular, I find Schubert’s Symphony No. 3 in D major to be seriously underrated. This is an intricately crafted work with purity of lyricism, strikingly original melodies and showcases Schubert’s individual style. Like the Hammersmith & City line, Schubert’s music may be an acquired taste, but it undoubtedly has its unique features that should not be neglected.

Metropolitan Line

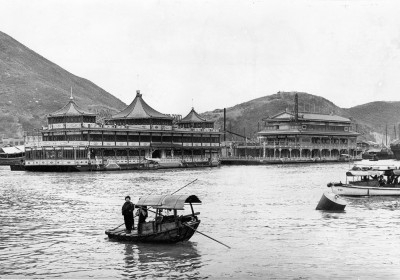

The Metropolitan Line is the oldest underground railway in the world, having begun operations back in 1863. It is also just one of two London Underground lines that cross the Greater London boundary, with branches to Chesham and Amersham in Buckinghamshire as well as one to Watford in Hertfordshire. The most interesting feature of the Metropolitan Line, perhaps, is that not all its trains will stop at every station along the line. In morning and evening peak hours (and also some non-peak times), the Metropolitan Line runs Fast and Semi-Fast services that not only bypass certain stations but also dramatically reduces passengers’ journey times. This service pattern, coupled with the long distance between stations, means that Metropolitan Line trains, known as S8 Stock, could reach the system’s highest permitted speed of 100km per hour.

Travelling on the Metropolitan Line has always been a pure joy. The trains are rarely packed and it is not uncommon for a passenger to be able to have up to four seats to themselves, allowing one to feel as though they were travelling Business or First Class on flights. It is particularly exciting to breeze past crawling Jubilee Line trains in northwest London when both lines travel in adjacent parallel tracks. A colleague of mine even once joked that the Metropolitan Line is the closest thing to high-speed rail in Britain, given how our actual high-speed rail lines are always subject to delays and cancellations.

Thanks to the Metropolitan Line’s speed, its dazzling scenery en route and the very fact that it transports passengers from the bustling capital to the tranquil home counties, I always have a jovial holiday mood whenever I travel onboard one of its trains. This mood is encapsulated in the first movement of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 in A major, especially at the beginning of the Vivace section. The excitement, enthusiasm and a certain degree of mystery embodied within Beethoven’s score are unrivalled in the repertoire and this work also seemingly symbolises the beginning of an adventure, just as a journey on the Metropolitan Line does.

Bakerloo Line

Opened in 1906, the Bakerloo Line is coloured brown on the tube map and runs between London’s north-west suburbs to inner city London. Originally, this line was called the Baker Street & Waterloo Railway. A contemporary journalist, however, used the contraction of ‘Bakerloo’ in his articles and this nickname promptly caught on in English society. By the summer of 1908, Bakerloo became the official name of the line and has remained ever since.

The current trains being used on the Bakerloo line are those of the ‘1972 Stock’ which, unsurprisingly, have been in use since 1972. These are the oldest trains in passenger service all across Britain and they have a very retro-looking interior. Every time I stepped onboard these carriages, I felt as though I was transported back in history and entered a totally different epoch. The interiors are dated, the seats have all seen better days and the doors often have a squeaky sound to them. However, despite these shortcomings, the railway vehicles still function exceptionally well. Although they have been operating for more than 51 years, the carriages are as sturdy and as reliable as ever, and they serve as a retro and nostalgic reminder of London Underground’s heritage. And unlike the majority of Tube lines, the Bakerloo Line is manually controlled and has a relatively slow speed, further adding to its old-school, low-tech character.

As such, the Bakerloo Line always reminds me of Sergei Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 1 in D major, nicknamed Classical, a work, despite being composed in the 1910s, was thoroughly written in the style of the masters of the Classical era. In the words of Prokofiev, he aimed to write ‘a symphony as Mozart or Haydn might have written it […] had either one of them been a contemporary’. This neoclassical work harkens back to a simpler, purer era and reminds one of the glories of the past, just as the Bakerloo Line trains do with their wistful appearance.